Part 2: An overview of modern plant breeding techniques and their advantages

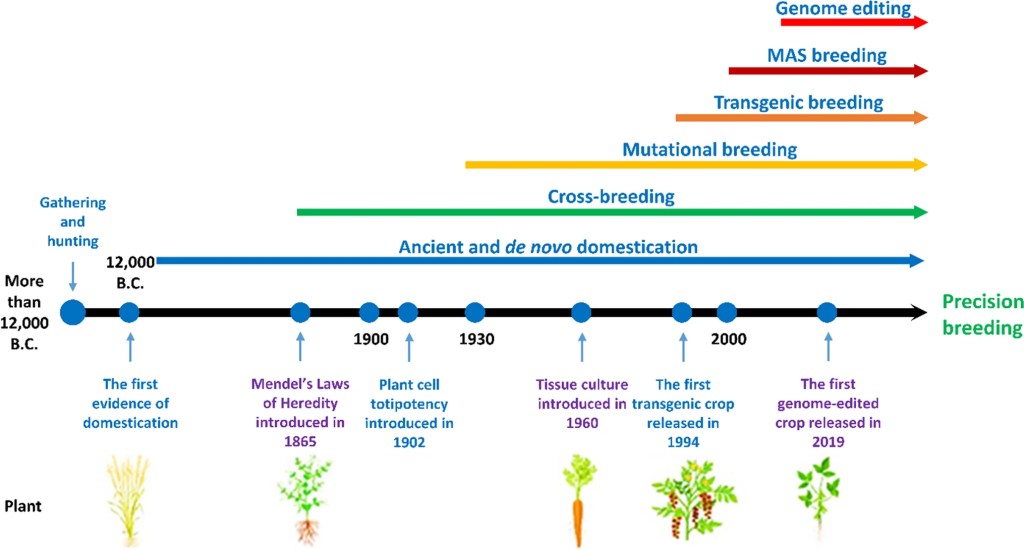

Approximately 12,000 years ago, humanity began a transition that would lead to a fundamental change in the way people live. Independently of each other, populations in 11 different regions spread across the world began the slow process of moving from nomadic hunter-gatherer societies to sedentary agricultural communities. This process, called the Neolithic Agricultural Revolution (1), has since defined every aspect of the modern world.

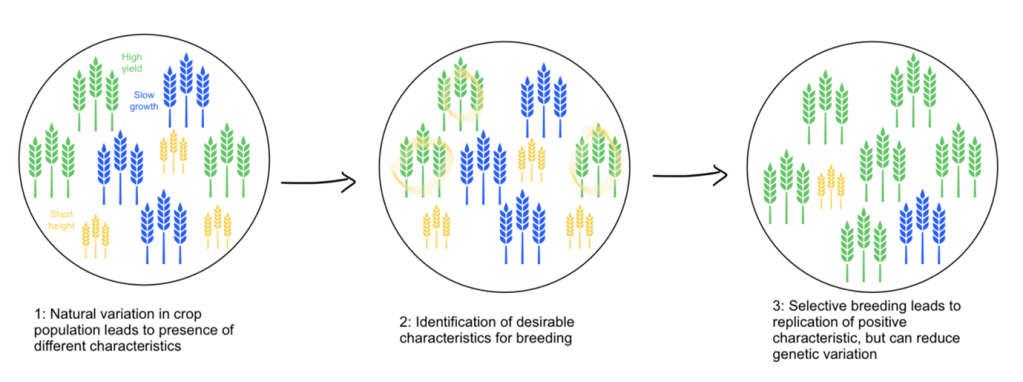

For almost as long, humans have been involved in genome engineering. Even though the Neolithic farmers didn’t know they were doing it, they were able to domesticate certain plant species by modifying their genetics. Farmers initially achieved this through selectively planting the seeds of plants with desirable characteristics, while disregarding crops deemed as unsuitable. Like animals, plant populations exhibit significant diversity, even within species. Two different wheat plants may be different sizes, produce varying amounts of grain, taste different, ripen at distinct rates, be harder or easier to harvest, and so on. These differences are due to genetics. Genetic information is encoded in DNA, a macromolecule that acts similarly to the computer code in the device you are reading this article on. DNA dictates how plants grow, what they look like, how fast they reproduce; it contains all the necessary information that the plant needs to survive. However, not all plants contain the same information. DNA is liable to changing, or mutating, over time due to environmental stresses, errors in replication, and myriad other factors. When these mutations are not corrected, they can have a disruptive effect on how a plant develops. Sometimes these mutations are negative, leading to the death or sterility of a plant; often these changes have no or minimal effect, and it is impossible to tell from the outside that they have happened at all; but occasionally, these mutations can have a positive effect, such as causing the crop to produce more grain.

When considering the entire population of a plant species, the total number of these differences is referred to as the genetic variation. The higher the level of genetic variation, the more differences there are between individual plants. These differences provide the basis for selection by farmers as they result in desirable physical characteristics, as well as negative traits that are selected against. Therefore, we can consider genetic variation to be the source of positive characteristics selected for in domestication.

Neolithic farmers were not solely focused on plants producing bigger yields. They also selected against plants with bitter or smaller seeds, while faster maturing plants with seeds lost before harvest were also unavailable for planting in subsequent seasons. Founder crops such as wheat and barley began to undergo genetic changes in their populations, favouring crops that produced larger, tastier grain which was retained for longer by the mature plants. The process of producing plants with characteristics suitable for use in agriculture is known as crop domestication.

Crop domestication allowed farmers to genetically refine their plants, producing fields of crops with higher yields. However, this also came at a cost: as a population of crops becomes increasingly genetically similar, its resilience to external stressors is reduced. Plants with similar phenotypes (observable traits) display similar responses to stress. In a population with low levels of genetic variation, a disease capable of killing one plant is likely to spread rapidly, which can wipe out most or all of the yield. Similarly, if one plant is unable to survive its environmental conditions, for example due to drought, other plants in the population may also struggle to survive if they are found within the same environment.

Herein lies an inherent problem for modern agriculture. On one hand, the creation of highly productive elite crops through domestication is required to optimise yields and produce sufficient food. However, the resulting low level of genetic variation increases the risk of a catastrophic stressor wiping out most of the yield simultaneously. Thousands of years of crop domestication has meant that elite crops today display very low genetic variation, meaning that they perform highly efficiently but only within a narrow range of environmental conditions. Fluctuations in these conditions can limit crop yields by inhibiting grain production, or in extreme cases by causing crop death. The common agricultural practice of planting monocultures can further increase the risk of crop failure by facilitating the rapid spread of disease between vulnerable plants.

As discussed in part 1 of this series, climate change is anticipated to place significant pressure on crop production over the 21st century, as weather patterns become more unpredictable, extreme weather events become more frequent, and knock-on effects lead to changes in the spread and frequency of plant diseases. Simultaneously, the increase in global population will continue to drive demand for food while yields plateau or decline. Under these conditions, the elite crop varieties of the 20th century will no longer be sufficient to meet the needs of our changing world. Furthermore, conventional intensive farming practices produce significant greenhouse gas emissions, meaning that in their current form they cannot form part of a long-term solution.

To meet the agricultural challenges of the 21st century will require us to create the next generation of elite crop varieties. We will need resilient plants that can survive drought, flooding, pests and disease, all while requiring less fertilizer and less maintenance. The crop varieties of the 21st century will be plants our neolithic ancestors could have only dreamed of. Fortunately, modern genetic technologies may hold the key to unlocking a healthier, more productive and more reliable food source. In this article, we will examine four different plant breeding techniques that could be used to secure our food of the future, and briefly discuss their different strengths and limitations.

New breeding techniques are making genetic engineering more efficient

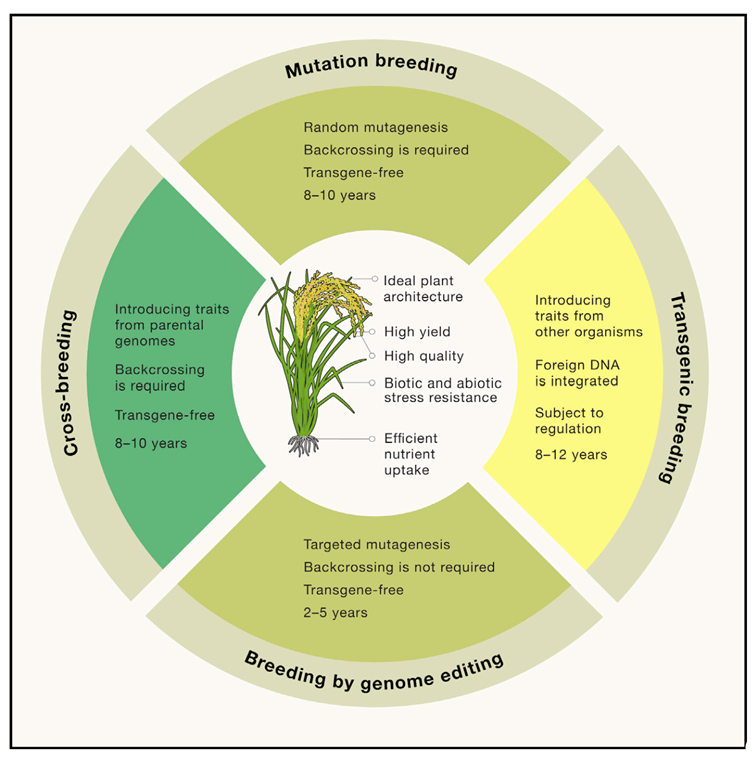

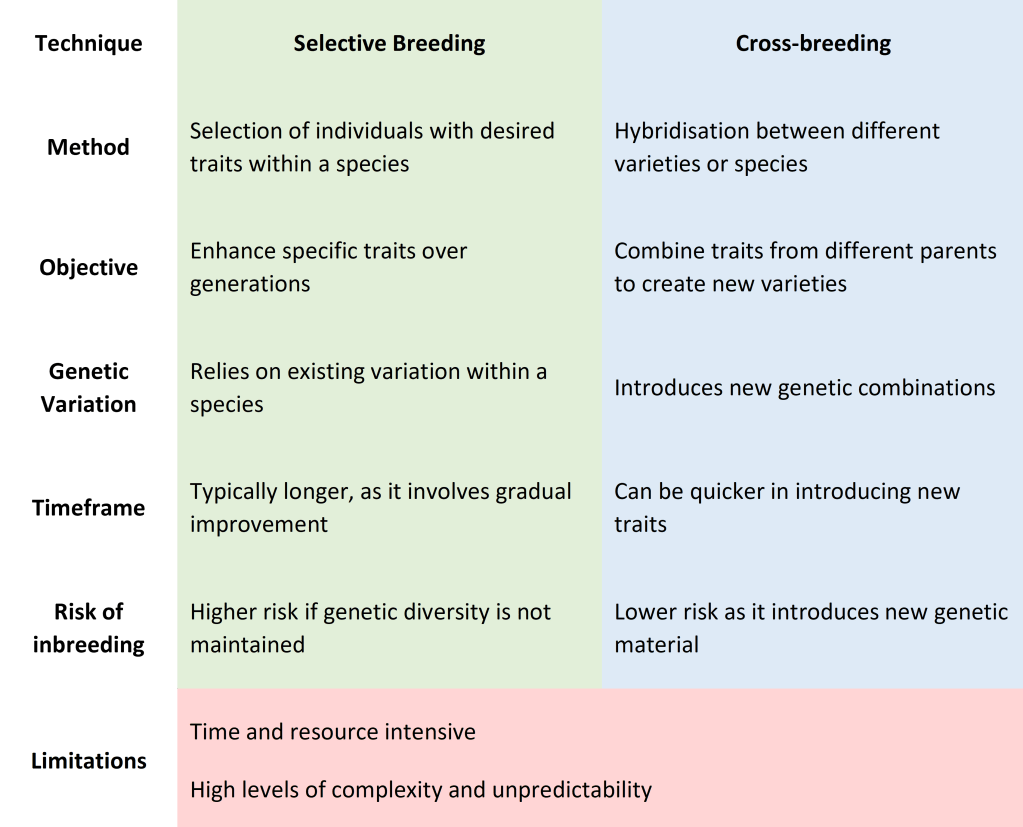

Selective breeding has been used to domesticate plants through the replication of desirable traits from parental genomes. This technique has been historically effective in the generation of elite crop varieties but has several limitations. Selective breeding is time-consuming, typically requiring multiple generations of plants to be raised before the desired trait(s) are widely spread through the population. As mentioned earlier, it also leads to reduced genetic diversity due to in-breeding, which can make plant populations more vulnerable to diseases or changes in environment. Finally, modification of species is limited to the selection of naturally-occurring traits – farmers are not able to introduce new traits at will, but instead can only pick from those present throughout their founding crop population.

Despite these limitations, selective breeding was highly successful in generating multiple elite crop varieties over thousands of years. Farmers across the world used selective breeding to domesticate different varieties of barley, rye, wheat, rice, lentils, and other staple crops. However, starting in the mid-19th century, a greater understanding of genetics and wider experimentation has led to the development of other breeding techniques for the modification and domestication of plant species. These include cross-breeding, mutation breeding, transgenic breeding, and most recently, breeding with genome editing.

Cross-breeding

Cross-breeding involves the intentional hybridization of two different plant varieties or species to combine desirable traits from both parents into a single new variety (4). This method is often used to introduce new traits that are not present in the existing gene pool of a single species, expanding the scope of genome engineering beyond the traits present in a single plant species. Cross-breeding can result in hybrids that possess a combination of traits such as improved yield, resistance to pests and diseases, or adaptability to different environmental conditions.

The development of cross-breeding in agriculture was reliant on Mendelian genetics, which provided the foundational principles for understanding inheritance patterns. Gregor Mendel’s work on pea plants in the mid-19th century established the basic laws of inheritance, such as the laws of segregation and of independent assortment of genes. These principles are essential for predicting the outcomes of cross-breeding experiments, as they help scientists understand how traits are passed from one generation to the next. This enabled the creation of crop varieties with new traits combined from different plant varieties or species, including those not present in a single species. The introduction of genetic material from other plants also allowed scientists to circumnavigate one of the key limitations of selective breeding, namely the reduction of genetic diversity resulting from inbreeding. By mixing genes from different parents, cross-breeding can be used to increase genetic diversity in the offspring population, which can enhance crop population resilience to diseases and environmental changes.

Cross-breeding began to be used extensively as a method to improve plant species after the rediscovery of Mendel’s work around the turn of the 20th century (5). Mendel’s principles allowed breeders to systematically combine desirable traits from different parent plants to produce offspring with improved characteristics. However, high levels of complexity and unpredictability associated with the cross-breeding remains a key limitation of this technique. Often, extensive backcrossing is required to stabilise the prevalence of desired traits, which also makes cross-breeding a time and resource intensive technique. Furthermore, the unpredictability of outcomes can also lead to the unintended introduction of unwanted traits; just as novel beneficial traits can be introduced, offspring plants may also develop novel detrimental traits that require further breeding efforts to eliminate.

| Backcrossing – Backcrossing is the process of breeding offspring plants with one of its parents possessing the desirable characteristic, to incorporate it into the hybrid offspring – The resulting offspring is called the backcross generation. Members will exhibit a genetic makeup representing a mix of the parental and hybrid genomes. The individuals from this backcross generation that display the desirable characteristic most strongly are selected – The process is repeated using the hybrid plant as the new parent. Backcrossing is – iterated over several generations, with the exact number varying depending on the complexity of the trait – This allows the proportion of desired genetic material from the chosen plant to increase over cycles, while undesirable alleles are progressively diluted |

While the development of cross-breeding has allowed scientists to overcome some of the limitations of selective breeding, both techniques remain highly unpredictable, as well as time and resource intensive. The identification of positive traits requires a lot of time, as each plant in the crop population needs to be screened. These traits then need to be bred into offspring, and often stabilised through multiple generations of backcrossing. While these techniques do allow for the creation of elite crop varieties, it can take decades of painstaking labour to achieve them. This limited the ability of our ancestors to generate novel crop varieties, and motivated scientists to continue searching for more efficient breeding techniques.

Mutation breeding

While selective breeding and cross-breeding have allowed scientists to increase the presence of positive traits in crop populations and introduce new traits into crops from other plant species, both methods are limited in that they can only introduce or amplify naturally-occurring traits. If a desired trait doesn’t naturally exist within a relevant plant population, these techniques can’t introduce it into a crop variety. To circumvent this limitation, scientists began looking for alternative breeding techniques to increase the mutation frequency of plants and hence increase the presence of novel traits in plant populations. After the second World War, interest in other applications of atomic energy led scientists to begin exposing various crops to X-ray and Gamma radiation with the aim of generating novel positive traits by luck. As recounted by nanotechnology researcher and historian Paige Johnson, “[o]ne of the ideas was to bombard plants with radiation and produce lots of mutations, some of which, it was hoped, would lead to plants that bore more heavily or were disease or cold-resistant or just had unusual colours. The experiments were mostly conducted in giant gamma gardens on the grounds of national laboratories in the US but also in Europe and countries of the former USSR.” (6)

Mutation breeding involves the random introduction of mutations into a crop plant’s genome, through exposing plant seeds or tissue to radiation or chemical mutagens. Mutagens are capable of damaging the DNA in the plant cells. They can induce a number of changes in the genetic material of these cells, including single-point mutations, small insertions or deletions, or larger scale structural reorganisations. DNA mutations result from the repair of damaged genetic material, as the repair pathways employed by the organism can often make small mistakes. The mutation rate is therefore variable depending on the fidelity of the repair pathways, the crop species, and the mutagen(s) used.

The random nature of the mutations created can allow for the generation of characteristics that do not occur naturally, as well as the recovery of those lost in the process of evolution. It also increases the genetic variety amongst the exposed crop population and can facilitate the creation of novel genes and gene functions where none can be found. Therefore, this technique broadens the range of positive characteristics that can be selected for, allowing for generation of a broader range of novel phenotypes in crop species. In essence, this allows scientists to introduce non-naturally occurring traits into crop populations. Furthermore, mutation breeding can also be used to enhance seedless crop varieties, such as bananas or root vegetables, where other breeding approaches may not be viable. This expands the range of the technique to cultivars that otherwise may be difficult to improve (7).

Another advantage of mutation breeding is that it does not involve the introduction of foreign genetic material, unlike transgenic breeding. This can be advantageous in countries where genetically modified organisms (GMOs) face regulatory and public acceptance hurdles for bringing a new crop to market, although this is not always the case. Despite the lack of foreign genetic material, crops developed through mutation breeding are sometimes still subject to additional regulation. For example, Canada requires plants developed through mutation breeding to be subject to regulatory oversight as “Plants with Novel Traits” (8). This classification can impact testing requirements and the commercialisation process for new crop varieties.

Despite these advantages, mutation breeding is limited by the random nature of the mutations it creates. If modern genetic editing techniques are making precise incisions in a genome with genetic scissors, mutation breeding is blasting the genome with a shotgun. The mutations are not targeted, meaning that it can be difficult to elicit significant changes in desired traits as the underlying genes are not necessarily affected. Furthermore, use of multicellular organisms in mutation breeding can lead to chimeras, where a mutation found in part of the organism is not present across the entire genome (9). This can lead to issues when identifying or stabilising the presence of a positive characteristic across a crop population, as genetic instability in chimeric plants can lead to unpredictable trait expression and inheritance patterns.

Another limitation for mutation breeding is, as with selective and cross-breeding, the requirement for a period of backcrossing to isolate and stabilise positive traits after their introduction. While the high mutation frequency can allow for the introduction of non-natural novel characteristics at a faster rate than traditional breeding methods, the reliance on backcrossing can make mutation breeding a resource- and time-intensive process, limiting the efficiency with which positive traits can be introduced. Combining mutation breeding with modern molecular techniques has allowed for the acceleration of some steps in the breeding process; for example, high-throughput genome sequencing has expedited the screening process. However, substantial work is still required to grow, screen, and stabilise positive characteristic presence amongst crop populations.

Transgenic breeding

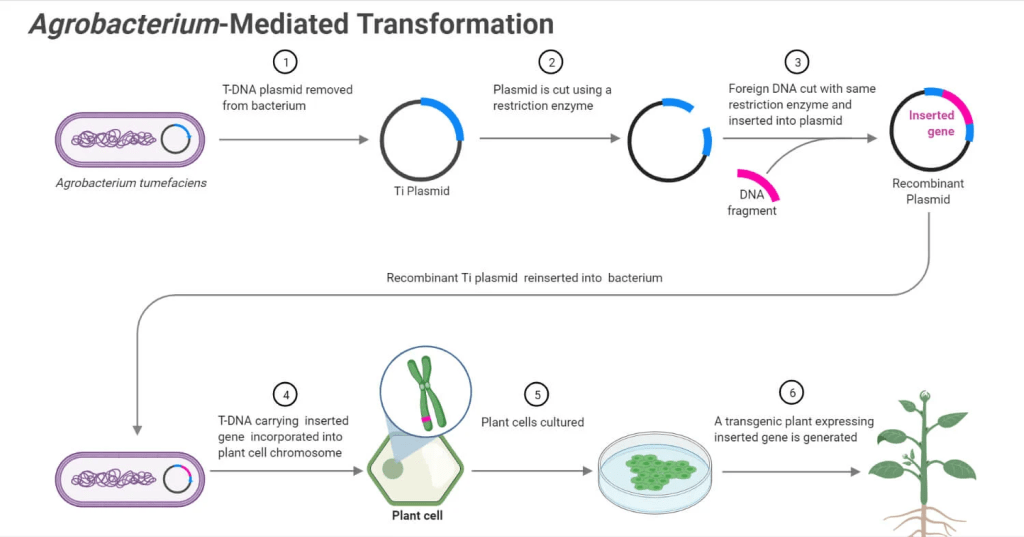

Another technology employed to generate non-naturally occurring characteristics in crop plants is transgenic breeding. This technique generally utilises modified Agrobacterium, a plant pathogen capable of inserting DNA into plant genomes, to facilitate the transfer of genetic material from one organism into the genome of a separate crop species. This is done to enhance a crop plant in some characteristic(s), such as increasing resistance to a stressor or improving crop yields.

Unlike cross-breeding and mutation breeding, transgenic breeding doesn’t require extensive backcrossing to remove undesired genes as the approach allows the selection and insertion of only the desired alleles (10). Using molecular markers allows the integration of the elite cultivar with transgenic hybrids in as few as 2 generations (11). This allows for faster generation of crops with desired characteristics and makes this approach compatible with plants that have long breeding cycles. Furthermore, transgenic breeding also broadens the range of non-naturally occurring characteristics that can be introduced into crop plants by allowing the use of genetic material derived from a much wider range of organisms, including microbes.

Unlike traditional breeding methods and mutation breeding, transgenic breeding leverages pre-existing understanding of plant genomics and modern gene editing technologies to make changes to plant genomes. This means scientists have much greater control over the types of trait(s) being introduced and can introduce specific desirable characteristics to plant cultivars at will, although this requires a much more in-depth understanding of the targeted gene(s) function as well as the identification of desired alleles.

While transgenic breeding allows for selection of the features of the introduced trait, Agrobacterium-mediated integration of exogenous DNA is inherently random (12). This means that the gene for the desired trait is inserted into the crop genome at random loci, potentially leading to disruption of other gene functions. Insertion of DNA via Agrobacterium is therefore prone to random chance off-target effects, unintended consequences, and low precision gene integration. This requires verification of gene functionality post-insertion but may also require screening of crops post-editing to ensure other desired traits have been retained and unaffected by the insertion of new DNA.

Transgenic crops, also known as genetically modified organisms (GMOs), are also subject to much higher levels of regulatory scrutiny than cis-genic crops, as well as higher levels of stigma amongst the general population surrounding the ethics and safety of them. These regulatory hurdles are largely intended to reduce the risk of unintended consequences such as horizontal gene transfer (the transfer of genetic material from GMOs to non-target organisms) and ensuring the overall safety of GMOs for consumption and the environment.

While regulatory requirements are beneficial and necessary for product safety, navigating them increases the time to market for new crops, as well as the price tag associated with their creation. Buttressing this is the fact that transgenic breeding is a very complex process, requiring expensive equipment and significant expertise. This limits the application of this technique to economically advantaged nations that have the required resources and a highly educated workforce – the same nations that already benefit from higher levels of resilience to climate change.

Breeding using Genome Editing (GE breeding)

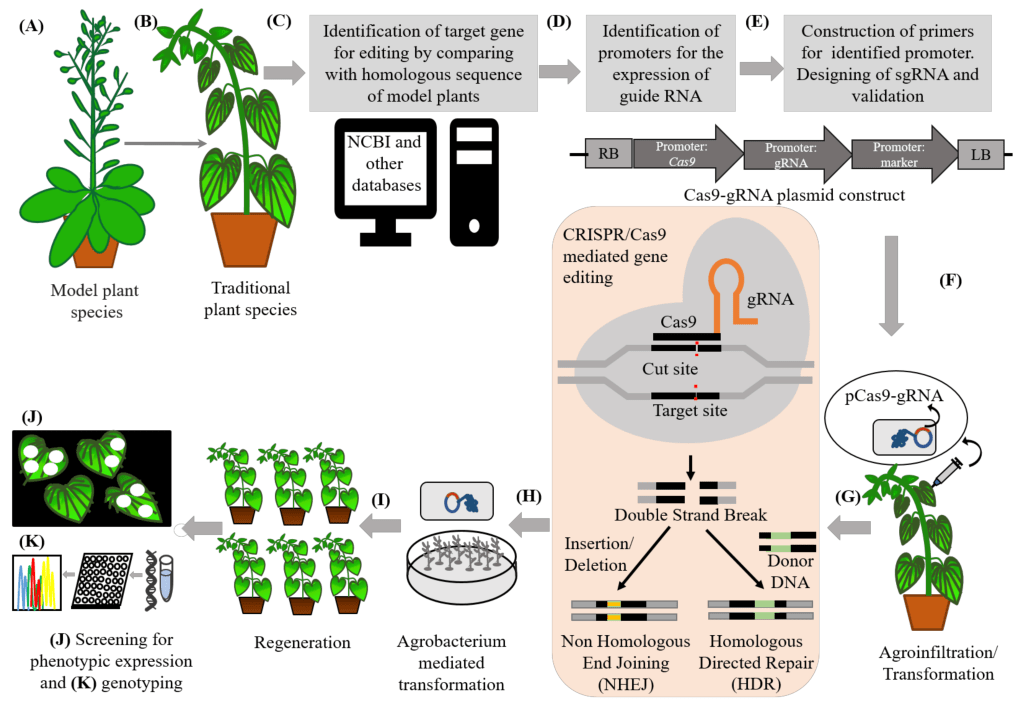

GE breeding can introduce targeted changes to specific gene(s) or gene functions in a plant genome, enabling the introduction of desired characteristics. Like transgenic breeding, GE breeding also does not require extensive backcrossing, dramatically increasing the efficiency with which desired characteristics can be achieved. Removing the requirement for backcrossing using GE breeding can reduce the time taken by nearly two-thirds (13) compared to cross-breeding or mutation breeding approaches. CRISPR-Cas technologies also allow for multiplex trait-stacking the editing of multiple genes simultaneously, allowing multiple desired traits to be introduced in a single generation and further accelerating the plant breeding process compared to traditional methods.

GE breeding does not rely on Agrobacterium to modify genetic material. Instead, CRISPR, Zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs), or other genome editing tools are employed to make direct changes to the plant genome. Using these tools negates the requirement for inserting foreign DNA into the plant genome, which carries a higher risk of unintended consequences and have higher potential to destabilise the genome. Furthermore, the changes introduced in GE breeding are often only a few nucleotides long, making them difficult to distinguish from naturally occurring mutations. For these reasons, genetically edited plants are considered safer than GMOs, and in countries where GMO crops are permitted (notably including the US and Canada) GE crops face a relatively light regulatory environment. Specifically, the transgene-free nature of GE crops often exempts them from the scope of existing GMO regulations. However, in the European Union GE crops are still subject to strict regulations following a 2018 ruling by the European Court of Justice (14), which extended the bloc’s strict regulatory framework for genetic engineering to so-called new genetic technologies (NGTs). This limits the bloc’s ability to use modern genetic editing techniques to generate novel crop varieties, potentially increasing European reliance on international research for food security.

The most widely used genome editing tool, known as CRISPR-Cas, is highly accurate and relatively inexpensive to use. Developed in 2012 by Jennifer Doudna and Emanuelle Charpentier, CRISPR-Cas tools are “genetic scissors” that can be used in almost any lab with almost any crop. This has expanded the range of genetic engineering to plants not easily bred with conventional methods. The high accuracy of CRISPR-Cas also reduces the risk of off-target edits, meaning that the frequency of unintended mutations in the genome is similar to the frequency of naturally occurring mutations. This is substantially less than in mutation breeding, in which the rates of mutation can be 1000X higher than natural mutation frequency (15). The adaptability and affordability of CRISPR-Cas and similar technologies make them accessible to a wide range of laboratories, potentially democratising the development of improved crop varieties across the world. This is particularly notable for countries in South America and sub-Saharan Africa, which are likely to suffer particularly significant losses of arable land. The adaptability of CRISPR-Cas technologies may enable scientists working in these countries to focus on regional staple crops, reducing their reliance on international research into staple crops grown by wealthy countries. With GE breeding, scientists can address specific agricultural challenges, such as disease resistance and climate adaptability, with a speed and specificity previously unattainable. These advancements offer hope for regions facing food scarcity and environmental constraints, particularly as demand for sustainable and nutritious food sources grows alongside the global population. A few landmark studies have already highlighted the potential crop improvements CRISPR-Cas tools may bring to bear. CRISPR-Cas systems have been used to generate pathogen resistance in bananas (16), potatoes (17), barley (18), and other crop varieties (19). Similarly, increased crop resilience in the face of adverse growing conditions has been achieved in a number of species, such as in drought-tolerant maize (20), or cold resistant wheat and rice (21). However, the scope of CRISPR-Cas techniques is not limited to improving crop resilience. Increased yield and improved crop architecture has been demonstrated in rice (22), wheat (23), and other species. It is also possible to increase the nutritional benefits associated with crops by modifying their biosynthetic pathways. Scientists have successfully generated high-fibre wheat varieties, high lycopene tomatoes, and increased the starch quality in sweet potatoes (24). These studies highlight the potential of GE crops for combatting global malnutrition, not only caloric insecurity through increased yields.

Conclusion

Plant breeding techniques have advanced tremendously since the early days of selective breeding by Neolithic farmers. Advancements in our understanding of genetics, biochemistry, and new genome engineering technologies have driven an exponential improvement in plant breeding. Each successive method—whether cross-breeding, mutation breeding, transgenic breeding, or genome editing—has expanded the toolkit available to scientists and farmers, allowing them to address a growing range of agricultural challenges. Soon, scientists may be able to leverage other cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence and quantum computing to parse massive bioinformatic databases with incredible precision and speed, unlocking new realms of agricultural improvement.

Genome editing technologies, especially CRISPR-Cas technologies, stand out as a promising future direction due to their precision, accessibility, and relatively low cost. Furthermore, they democratise breeding capabilities, allowing a wider range of regions to develop solutions tailored to local crops and conditions, which is crucial for global food security. By enabling targeted, efficient modifications without the introduction of foreign DNA, genome editing offers a balanced approach to improve almost any crop, but regulatory hurdles and issues surrounding public acceptance remain. Any solution of the food insecurity caused by climate change will necessarily be multi-factorial, and strong cooperation between countries to establish scientifically-sound regulatory frameworks may present a higher barrier to genetic agriculture than technological ability in an unstable geopolitical world. Similarly, public acceptance of genetically altered crops will have to be bolstered through educational and promotional campaigns, particularly in regions where there has been historic hesitancy around genetically altering food such as in Europe.

Despite these challenges, the evolution of plant breeding can and will facilitate a shift toward more sustainable agricultural practices. Embracing these advanced breeding techniques can lead to more resilient crop systems that are better suited to withstand environmental pressures. The continued innovation in fields related to synthetic biology, coupled with responsible regulatory practices, will be key in ensuring the balance between productivity, environmental sustainability, and food security for future generations. By promoting international regulatory and scientific cooperation, we can harness these innovations responsibly and equitably, paving the way for a resilient agricultural system that can adapt to changing global conditions. Ultimately, the success of our efforts will depend on our ability to integrate scientific advancements with societal needs, and collaborate to ensure that the benefits of modern plant breeding are accessible to all regions and communities worldwide.

Glossary

Agrobacterium is a type of bacteria that naturally transfers genes to plants. Scientists use this bacterium to insert specific genes into crops for genetic modification purposes.

An Allele is a specific version of a gene that can create different traits in an organism, like colour or size. Each parent contributes one allele for every gene, impacting the traits seen in the offspring.

Backcrossing is a breeding method in which offspring are repeatedly bred with one of their parents to enhance specific desired traits.

Crop Domestication is the process of adapting wild plants for human use through selective breeding across generations. This process encourages traits like larger seeds, improved taste, and higher yield, transforming wild plants into crops that thrive under cultivation and meet human needs more effectively.

CRISPR-Cas is a highly accurate gene-editing tool that acts like molecular scissors, allowing scientists to make precise changes to specific genes in an organism.

Genetic Variation represents the range of genetic differences within a species. A higher level of genetic variation creates more diversity in traits, which helps plants better adapt to environmental stresses.

Genome Engineering is the process of modifying an organism’s genetic material, or DNA, to alter its characteristics. This technique is often used to improve traits such as crop yield or resistance to diseases.

Horizontal Gene Transfer is the movement of genes between different species, which can happen naturally or be facilitated by genetic engineering. In agriculture, it is sometimes used to introduce beneficial traits across species.

Monoculture is the agricultural practice of growing a single type of crop across a large area. This approach can increase vulnerability to diseases because of reduced genetic diversity in the crop population.

Multiplex trait-stacking is the process of combining multiple beneficial traits into a single crop variety at the same time.

A Mutation is a change in DNA that may lead to new traits in an organism. Mutations occur naturally, but scientists can also induce them to introduce beneficial traits in crops.

Mutation Breeding is a technique where plants are exposed to radiation or chemicals to induce random genetic changes. The goal is to produce beneficial new traits, although the changes are unpredictable.

Phenotype refers to the observable characteristics or traits of an organism, such as its height, colour, or resilience to disease. These traits are determined by the organism’s genetic makeup.

A Transgene is a gene that has been transferred from one species to another. In plants, this allows for the introduction of traits that do not naturally occur in the species, such as pest resistance.

Bibliography

- Blakemore, E. (2019) What was the Neolithic Revolution? National Geographic. Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/neolithic-agricultural-revolution.

- Van Vu, T. et al. (2022) ‘Genome editing and beyond: what does it mean for the future of plant breeding?’, Planta, 255(6). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-022-03906-2.

- Gao, C. (2021) ‘Genome engineering for crop improvement and future agriculture’, Cell, 184(6). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.005.

- Wieczorek, A. and Wright, M. (2012) History of Agricultural Biotechnology: How Crop Development has Evolved | Learn Science at Scitable, Nature.com. Available at: https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/history-of-agricultural-biotechnology-how-crop-development-25885295/.

- Saleh, G. (2015) ‘Crop breeding: exploiting genes for food and feed – Universiti Putra Malaysia Institutional Repository’, Upm.edu.my [Preprint]. Available at: http://psasir.upm.edu.my/id/eprint/18233/2/INAUGURAL%20PROF%20GHIZAN.PDF.

- Atomic Gardens (no date). Available at: https://pruned.blogspot.com/2011/04/atomic-gardens.html.

- Ali, S. and Talekar Nilesh Suryakant (2024) ‘Mutation Breeding and Its Importance in Modern Plant Breeding: A Review’, Journal of Experimental Agriculture International, 46(7), pp. 264–275. Available at: https://doi.org/10.9734/jeai/2024/v46i72581.

- Rowland, G. (2022) The effect of plants with novel traits (PNT) regulation on mutation breeding in Canada, Iaea.org. Available at: https://inis.iaea.org/search/search.aspx?orig_q=RN:40020730

- Jankowicz-Cieslak, J. et al. (no date) Biotechnologies for Plant Mutation Breeding Protocols. Available at: https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/28039/1/1001957.pdf#page=54

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens and genetic engineering – microbewiki (no date) microbewiki.kenyon.edu. Available at: https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Agrobacterium_tumefaciens_and_genetic_engineering.

- Kundu, V. (2024) ‘Transgenic Breeding’, pp. 14–34. Available at: https://doi.org/10.58532/nbennurch218.

- Gelvin, S.B. (2021) ‘Plant DNA Repair and Agrobacterium T-DNA Integration’, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(16), p. 8458. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22168458.

- Pixley, K.V. et al. (2022) ‘Genome-edited crops for improved food security of smallholder farmers’, Nature Genetics, 54. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-022-01046-7.

- Gelinsky, E. and Hilbeck, A. (2018) ‘European Court of Justice ruling regarding new genetic engineering methods scientifically justified: a commentary on the biased reporting about the recent ruling’, Environmental Sciences Europe, 30(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-018-0182-9.

- Pixley, K.V. et al. (2022) ‘Genome-edited crops for improved food security of smallholder farmers’, Nature Genetics, 54. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-022-01046-7.

- ‘CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing of banana for disease resistance’ (2020) Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 56, pp. 118–126. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2020.05.003.

- Zhan, X. et al. (2019) ‘Generation of virus‐resistant potato plants by RNA genome targeting’, Plant Biotechnology Journal, 17(9), pp. 1814–1822. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13102.

- Kis, A. et al. (2019) ‘Creating highly efficient resistance against wheat dwarf virus in barley by employing CRISPR /Cas9 system’, Plant Biotechnology Journal, 17(6), pp. 1004–1006. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13077.

- Talakayala, A., Ankanagari, S. and Garladinne, M. (2022) ‘CRISPR-Cas Genome Editing system: a Versatile Tool for Developing Disease Resistant Crops’, Plant Stress, 3(100056), p. 100056. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stress.2022.100056.

- View of Engineering Drought Tolerance in Crops Using CRISPR Cas systems (2024) Horizonepublishing.com. Available at: https://horizonepublishing.com/journals/index.php/PST/article/view/2524/2546

- Li, Y. et al. (2022) ‘CRISPR/Cas genome editing improves abiotic and biotic stress tolerance of crops’, Frontiers in Genome Editing, 4. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fgeed.2022.987817.

- Verma, V. et al. (2023) ‘CRISPR-Cas: A robust technology for enhancing consumer-preferred commercial traits in crops’, Frontiers in Plant Science, 14. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1122940.

- Zhang, J. et al. (2021) ‘Increasing yield potential through manipulating of an ARE1 ortholog related to nitrogen use efficiency in wheat by CRISPR/Cas9’, Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 63(9), pp. 1649–1663. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/jipb.13151.

- Wang, H. et al. (2019) ‘CRISPR/Cas9-Based Mutagenesis of Starch Biosynthetic Genes in Sweet Potato (Ipomoea Batatas) for the Improvement of Starch Quality’, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(19), p. 4702. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20194702.

- Kumar, A. et al. (2021) ‘Integrating Omics and Gene Editing Tools for Rapid Improvement of Traditional Food Plants for Diversified and Sustainable Food Security’, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(15), p. 8093. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22158093.