I’ve been increasingly interested by AI over the last couple of years. This interest started about 9 months prior to the release of ChatGPT, as a friend introduced me to OpenAI’s GPT-3 model. While a fun tool to play around with, it was a bit too error-prone for any practical applications within my university studies. However, as we have seen the emergence of these commercial LLMs that seem poised to replace larger and larger chunks of the job market my interest in (and fear of) AI has deepened for all sorts of different reasons.

I think there is a real danger that we will end up in a “Sovereign Individual”-type dog-eat-dog world (1) where ordinary people basically end up powerless and living in abject poverty, while the upper echelons of societies control an exponentially increasing abundance of wealth and live in fenced off private communities. These fears are compounded by the fact that even anti-sovereign individualists are ringing alarm bells over other disruptive features of AI that could impact us all within the immediate future. In his book “The Coming Wave” (2), Mustafa Suleyman highlights the need for coordinated global regulation of AI research – while pointing out the many barriers that are likely to prevent this need being met. At the time of this article being published, the global trade war being unleashed by the current radical US president’s tariffs seems to highlight the unstable geopolitical context in which these tools are being improved at an exponential rate.

However, there are also some well-regarded voices of optimism within the field. My birthday is in late February, and as a gift (knowing that I’m interested in this sort of stuff) my dad gave me a copy of “The Future Is Nearer” by Ray Kurzweil (3). Kurzweil is an American computer scientist, futurist, AI-authority figure and techno-optimist, so it isn’t surprising that he holds a rosier view of AI’s potential than some of his contemporaries. However, I do believe that aspects of the world he envisions will come to pass, and some of this is cause for celebration. In particular, Chapter 6 of the book examines the fantastic potential for biomedical acceleration unlocked by the application of AI technologies to biomedical research.

As somebody with a background in Biochemistry and a passion for the Life Sciences, this was my favourite chapter. In this series of articles I want to discuss the transformative potential of AI-powered research for unlocking the answers to an intractable, universal problem: the treatment and mitigation of age-related diseases, physical and mental decline, and death. In this first article, I want to explore a few key questions, such as “What is ageing?”, “Why do we age?”, and “Should we do anything about it?”. I will then also explore an interesting concept introduced to me through “The Future Is Nearer”, namely the idea of Longevity Escape Velocity.

Amortality and Escaping the Reaper

Do you want to die?

I don’t mean right now, of course. I’m assuming that most of the people reading this article probably expect themselves to live a few more decades at least, or hopefully at least a few more years. However, my question stands – do you want to die?

My answer, like (I expect) most people, is yes. Nobody wants to significantly outlive all of their family, their friends, their neighbours and their community. Imagine a world wherein everyone you know today is long dead, and you are left alive, alone and confused in a world that you barely recognise. It sounds terrible.

But what if we changed the question? What if, instead of focusing on you as an individual, we offered an escape from death to everyone you love and care about? And what if we offered not just unlimited life, but also a healthier, younger self? Would you live for 500 years in the body of your 25-year-old self?

This imagined world is still a long way away, but these thought experiments are important because they shed light on the complicated field of gerontology, the study of ageing. This is a multidisciplinary field that straddles a fascinating border between biology, physics, ethics, psychology, sociology, economics, and more. As ageing is one of the fundamental, truly universal aspects of the human experience, it makes sense that studying ageing requires a lot of different lenses. The multi-faceted nature of ageing, along with the whole range of different cultural and ethical views surrounding nature, death, and purpose in life, mean that it will be very difficult for us to come to any true consensus about the answer to my question about amortality.

Despite this, I think there are some nearly universal unifying questions that can highlight areas in which we can agree (more-or-less) that progress should be made.

Do you want to develop Alzheimer’s? How about cardiovascular disease (CVD), or cancer? Would you wish these on your loved ones?

Obviously, nobody wants to be affected by these conditions – and yet, statistically speaking, it is almost guaranteed that you personally will be either directly or indirectly affected by them within your lifetime. If it isn’t your health that is affected, it could be a grandparent, a friend, a neighbour, a child. In the UK, where I live, Alzheimer’s and dementia is the leading single cause of death, representing about 11-12% of annual deaths (4). CVD is the largest combined killer, accounting for around 27% of annual deaths (5), although this top spot is closely contested by cancer, also around 27% (6). These three diseases therefore account for a combined annual total of approximately 66% of all deaths in the UK!

As many people can attest, these diseases are also unfortunately not pleasant ways to go. They are often characterised by long, accelerating declines, and can rob families of their members before they physically die. Each of these diseases is also linked to biological ageing, with the chance of developing them increasing with age. Why is this the case?

Biologically speaking, what is ageing?

Ageing is the accumulation of damage to cells, tissues, DNA, and other biological components that leads to the degradation of their function over time. One of my favourite descriptions of ageing is from biogerontologist Aubrey de Grey (more on him later). He describes ageing as a matter of physics. Over time, machines will accumulate damage and wear down. I like to think about this in a similar fashion to entropy. Entropy is the universal tendency for systems to move from a state of order towards a state of disorder. It is a fundamental principle of thermodynamics, and (as far as we can see) a universal phenomenon. A good example of this principle is imagining a sand-castle in a desert. We know instinctively that strong winds will degrade the sand-castle over time. However, technically speaking it should be physically possible for the wind to create a castle from the sand as well. The tendency of systems to move away from order (the castle) to disorder is highlighted by our instinctual rejection of this idea.

As with a sand-castle, the human body is a highly-ordered system. Countless numbers of metabolic functions need to be performed simultaneously, in concert and in perpetuity, for life to be viable. Everything from subcellular biochemical pathways to neurons firing throughout the nervous system to the autonomic regulation of the heart and lungs needs to work, and work well, for us to be alive right now. Over time, as the body performs its many functions, inevitably stuff goes wrong. Perhaps a failed DNA replication event causes damage to the genetic information contained within one of your cells, or you tear some muscle tissue while running too quickly. These events are big problems. The cell with damaged DNA could turn cancerous, or your torn hamstring might limit your ability to move and find food. Luckily, the body contains various highly effective repair mechanisms that allow you to quickly and accurately repair most forms of damage. Without the innate ability to repair damage at both macroscopic and cellular levels, your body (and so you) wouldn’t last very long. Entropy would slow turn your body into dust.

While these repair mechanisms are no doubt impressive, they unfortunately are not perfect. DNA repair mechanisms like homologous recombination and non-homologous end joining operate with astounding accuracy (estimated to be over 99.999%) (7), they do still make mistakes. This means that, over time, these mistakes accumulate. At first, you can’t notice that these mistakes have even occurred, but as they build up they begin to disrupt the normal functioning of the body. Muscle tissues become weaker. The skin doesn’t regenerate perfectly. Metabolism slows down, which can lead to health issues and weight gain. These physiological changes that we commonly refer to as “ageing” are actually mainly the result of the body slowly malfunctioning. Later in life, as the accumulated damage becomes significant this is manifested in the pathological conditions we recognise as “age-related diseases”. These are the same conditions that cause most deaths in developed societies today, and without further medical research and new treatments, they are also likely to affect you.

Welfare states and ageing populations don’t mix

In most economically affluent countries, there has been a long-term trend towards ageing populations. Ageing populations are those in which the proportion of older people increases relative to younger people, particularly those of working age. In most of Europe, North America, and parts of Asia, this has been the case for decades, driven by a falling birth rate and medical advances. Modern medicine now allows for the average person to live well into their 70s or even 80s. This is a good thing – it lets us enjoy more time with our parents and grandparents and allows them to have a well-deserved long retirement after a lifetime of hard work. However, while lifespans have increased significantly over the last century, healthspans unfortunately have not kept pace. The average healthspan is the length of time the average person can live without suffering from any significant or chronic health problems. It is a measure of quality of life, rather than duration.

Per capita healthcare spending increases dramatically with age

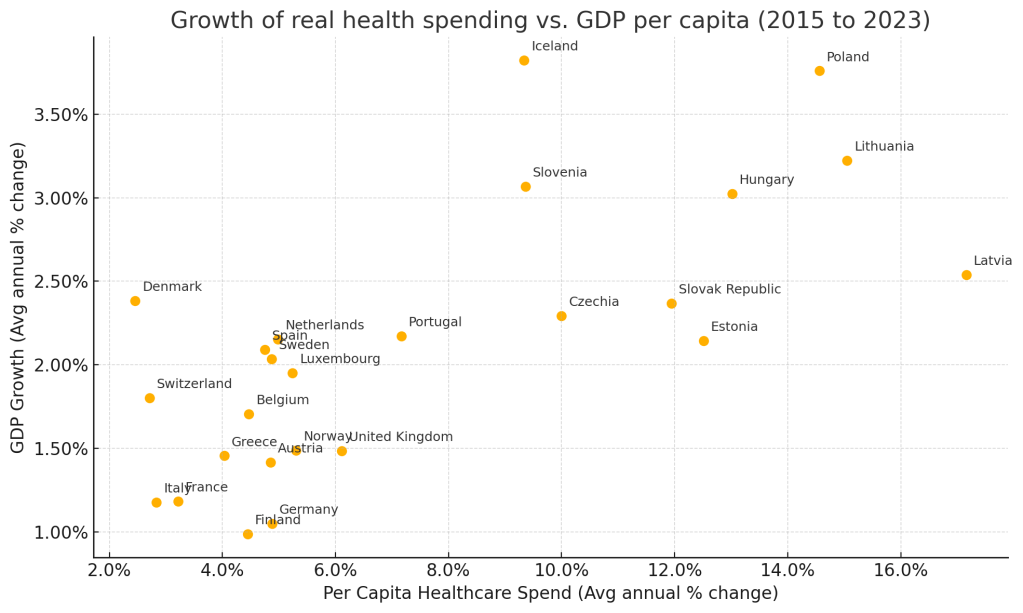

Growth in per capita healthcare spend has significantly outpaced GDP growth in nearly all European countries

The divergence between lifespan and healthspan presents us with a new societal challenge. As people get older, they tend to experience more significant and numerous health issues, requiring more medical treatment. This costs a lot of money and is a large driver behind the increase in health expenditure as a percentage of GDP that we have witnessed in most developed economies over the last few decades. This challenge is amplified by the falling birth rate, which has proportionally reduced young, working age population as families have fewer children. This increases the old-age dependency ratio (OADR; this is the proportion of retired people to working age people) in our societies, meaning that governments have to spend increasing amounts on healthcare while grappling with a shrinking taxation base. Economists will point to the universally prescribed capitalist panacea – economic growth. Having grown up in the UK over the first quarter of this century, I can attest to the fact that sustained and strong economic growth is by no means a guarantee in life.

Therefore, it seems to me that European and other developed economies have few options. We could spend less on healthcare, resigning our elderly to funding expensive treatments themselves or suffering if they cannot afford to do so. We could increase taxation on the working age population, making it yet more difficult for them to buy property and have fulfilling working lives (which could also drive down the birth rate, compounding the problem further). The third option is to funnel increasing amounts of funding into biomedical research, to combat this problem at the source. We must develop more effective preventions and treatments for age-related diseases, which will have the happy result of increasing our healthspans and decreasing our hospital bills.

Longevity Escape Velocity – It does what it says on the can

Longevity Escape Velocity (LEV) is a term first coined (as far as I can tell) by scientist and anti-ageing advocate Aubrey de Gray. De Gray is a (slightly controversial) British biogerontologist who believes that the distinction between age-related pathologies and the “normal” processes of ageing is an artificial one. Among others, De Gray has advocated for a “regenerative” approach to treating age-related diseases. Rather than addressing the symptoms of the diseases, at which point the cumulative damage to the body is too far gone to be meaningfully reversed or mitigated, regenerative medicine aims to address the root causes of these diseases by regenerating or restoring damaged cells, tissues, and organs. This field aims to augment our natural potential for healing through a variety of approaches, including stem cell therapies, gene therapies, and the use of senolytic drugs, among others. These treatments aim to slow and ultimately reverse the accumulation of age-related damage to our bodies, increasing our healthspans by actively combatting the biological hallmarks of ageing before they manifest as clinical pathologies.

When I first heard about regenerative medicine, I was initially sceptical. While the premise seemed to be logical, I had (and reserve) some doubts that we would really be capable of understanding our own messy, incredibly intricate biology with enough precision to be able to reverse a process with such widespread impacts while also not having catastrophic unintended consequences. However, as AI technology has emerged and progressed exponentially over the last few years, I have become increasingly convinced that the merging of biomedical science with AI computational tools may enable us to develop effective treatments to address biological hallmarks of ageing within my lifetime.

In “The Singularity Is Nearer”, Kurzweil introduces a concept named “The Law of Accelerating Returns (LOAR)”. The basic idea is that as technology gets better, it becomes more useful for designing new, better technology, which in can be used to design more new technologies, and so on. This forms an accelerating, exponential feedback loop that explains the rapid rate of progress witnessed in information technologies over the last few decades. Kurzweil believes that as our computational power and techniques advance, we will begin to handle the chaotic realm of bioinformatics and biology like another information technology. This, Kurzweil argues, will open biology and biomedical research up to the same LOAR cycle that has enabled such rapid advances in computation over the last ~80 years.

I personally have a few reservations over this idea. It isn’t immediately clear to me that biology can be used to design better biology in quite the same way that computer chips can be used to design better chips. Biological systems are much messier, less binary, less easily-quantifiable that computational systems, and I think that this barrier could mean that even if our biological understanding does grow at an exponential rate, this doesn’t necessarily imply a similar multiplier as we have seen with information technologies.

However, if we buy the premise that progress in biological understanding is entering an exponential loop, the smaller multiplier may not matter so much. Furthermore, if information technologies continue to grow at a strong exponential rate, this could have a resonance effect within biological research, wherein the exponential increases in computer power and algorithm advancement result in accelerated biomedical research even if our biological techniques or methods haven’t changed much. Simply increasing computational processing power could enable our existing bioinformatic tools to leverage larger, more complex datasets, even without algorithmic improvements.

Why is this important? Well, in my view these advances are likely to unlock many exciting research possibilities across diverse fields. As I have discussed in other articles, a more comprehensive understanding of genetic engineering could enable us to create better crops to mitigate climate change. However, these same genetic tools could also be used to repair DNA damage and epigenetic modifications, a key hallmark of ageing. Similar advances in other fields make the regenerative treatment of biological ageing more feasible, at an accelerating pace.

All of this brings me to the final concept I’d like to discuss in this article. Before we discuss this idea, I want to recap a few relevant points that form its basis:

- It is possible to regenerate biological damage and reverse hallmarks of ageing (reinforced by several interesting studies)

- Reversing these hallmarks is a more effective preventative approach to treating age-related pathologies than current symptomatic approaches

- The exponential progression of information technology will expand to biological research, allowing biology to enter a “law of accelerating returns”-style feedback loop that will cause biomedical research to advance at an exponential pace

- It may be more economically beneficial for countries to provide regenerative medical treatments to everybody than to restrict access to these treatments to the rich

If we buy the above premises, they imply an interesting phenomenon known as “Longevity Escape Velocity (LEV)”. This term was first coined by Aubrey De Gray, but the basic concept pre-dates this. The idea behind LEV is that, at some point in the future, the rate of biomedical advancement will be so rapid that each year new treatments will be developed that extend the average lifespan of humans for more than a year. This means that, for everyone treated, they could gain life-expectancy faster than they age (in a non-biological sense). If an individual or a population were to ever reach LEV, it would open the door to amortality. Amortality is the inability to die from biological ageing. Amortal individuals may still die from disease, accidents, or so on, but they do not die from age-related causes.

LEV is a fascinating concept because it challenges some of our fundamental beliefs about the way the world works. Many people are uncomfortable with the idea, believing that transcending ageing in this way is unnatural, potentially immoral and dangerous. Amortality raises complex ethical, moral, and religious quandaries. These concerns are all valid and warrant further consideration in future articles. I personally am still unsure whether:

- LEV is even possible – It may turn out to be a techno-optimist fantasy

- LEV is ethically acceptable or even sensible – The ramifications of stepping outside of the natural lifecycle of humans in such a significant way would have rippling n-order implications that could have serious revenge effects (e.g., compounding climate change impacts, causing new societal problems, especially if not implemented evenly)

However, I do also think there is sometimes a danger of believing that things that are “natural” are perfect and must be maintained at all costs. Natural selection, for example, while a brilliant process for optimising organisms for their environment is also a savage and brutal process that has caused untold animal and human suffering over millennia. There are also some interesting examples of amortal organisms that already exist in nature, most famously the Immortal Jellyfish (9). Does the existence of such creatures invalidate the view that death by biological ageing is a fundamental part of life?

Conclusion

If you have made it this far into this article, thank you very much! I’m planning to write a new series of articles focusing on biological ageing and treatments over the next few months, most of which will be in a more academic tone than this one. I hope you have enjoyed this discussion-style article – if you have, and want to see more in this style, please let me know at thenewscleus@gmail.com or message me/our page on LinkedIn!

Also, I haven’t forgotten about my climate change and agriculture series. I am researching my next article for that series and am aiming to have something out within the next month or so. Stay tuned and stay curious!

Bibliography

- “The Sovereign Individual”, James Dale Davidson and William Rees-Mogg (1997)

- “The Coming Wave”, Mustafa Suleyman (2022)

- “The Singularity Is Nearer”, Ray Kurzweil (2024)

- “Deaths registered in England and Wales: 2023”,Office for National Statistics (ONS) (https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsregistrationsummarytables/2023#leading-causes-of-death) Accessed 7 April 2025

- “What is the impact of CVD?”, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/cvd-risk-assessment-management/background-information/burden-of-cvd/#:~:text=Cardiovascular%20disease%20(CVD)%20is%20the,after%20dementia%20and%20Alzheimer’s%20disease.) Accessed 7 April 2025

- “Cancer: Summary of Statistics (England)”, House of Commons Library (https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN06887/SN06887.pdf) Accessed 7 April 2025

- Chatterjee, N., & Walker, G. C. (2017). Mechanisms of DNA damage, repair, and mutagenesis. Environmental and molecular mutagenesis, 58(5), 235–263. https://doi.org/10.1002/em.22087

- “Fiscal sustainability and public spending on health”, September 2016, Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) (https://obr.uk/docs/dlm_uploads/Health-FSAP.pdf) Accessed 7 April 2025

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turritopsis_dohrnii Accessed 7 April 2025