About a year ago, I wrote an article that discussed the morality behind eating meat. It’s a question that I still feel strongly about, yet it is only part of the conversation. For many, many, years, scientists, politicians, and activists alike have argued around plant-based diets for their potential as a climate change solution. This is an exhausted debate. Filled with dodgy deals and shadowing friendships the meat industry is here to stay and combined with the infighting within the scientific community, we are no closer to really answering this question. As I pondered this, I found myself thinking about plant-based diets beyond that of carbon emissions and land use. In doing so, I began to see their potential in a different light, peeling back the green hype to discover a deeper, more fascinating promise.

Setting the Scene

Understanding climate change is a complicated endeavour. Its effects have touched all corners of the globe leaving not just physical scars, but economic, social, and psychological ones too. As the anthropogenic contributions to this problem become cemented in science and history, we are driven by an urgent imperative to rectify our mistakes. Yet climate change’s pervasiveness, complexity, and broad, umbrella-term nature make the pursuit of “solutions” inherently fraught with political, ecological, and social tensions. Still, it is precisely in these uneasy spaces that progress is possible. Listening across divides can reveal shared ground and guide us toward more sustainable and just futures. And few domains are as heavily contested as that of agriculture.

The agricultural scientific narrative—exemplified by the IPCC—asserts that the global food system accounts for an estimated 20–30% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Crippa et al., 2021; IPCC 2019). By this metric alone, its role in climate change is substantial, a significance only magnified when considered alongside its contributions to biodiversity loss, land and water pollution, and deforestation (aan den Toorn, Worrell, and van den Broek 2020; Dudley and Alexander 2017). Notably, livestock alone produces an estimated 14.5% of anthropogenic emissions (Gerber et al., 2013), particularly beef which requires an average of 28 times more land and 11 times more water than pigs and poultry (Eshel et al., 2013). Given these impacts, modern agriculture holds a totemic status: it underpins contemporary society while simultaneously representing a major environmental challenge.

Consequently, this sphere has become a focal point in climate change mitigation. Various solutions have been proposed including feed additives like red seaweed (Kinley et al., 2020), organic farming (Scialabba and Müller-Lindenlauf 2010.), and alternative agricultural philosophies such as permaculture (Hathaway 2016) — yet none have garnered as much traction or controversy as plant-based diets (PBDs). This is because food choices are shaped by far more than just environmental reasoning. Factors such as convenience, availability, social norms, sensory preferences, moral responsibility, culture, and context all play a powerful role in determining dietary acceptability (Springmann et al., 2018). Reaching a definitive scientific consensus also remains complex. While numerous studies highlight the environmental benefits of PBDs – reporting reductions in GHG emissions, land use, and freshwater consumption (Fresán and Sabaté 2019; Hallström, Carlsson-Kanyama, and Börjesson 2015; Harris et al., 2020) – it is just as easy to find studies that rebuttal these claims (Macdiarmid 2022; Van Vliet, Kronberg, and Provenza 2020). This debate is hardly surprising, given the inherent complexity of modelling dynamic ecosystems and the immense financial influence and lobbying power of the agricultural industry.

As a result, traditional discussions around PBDs revolve around familiar environmental metrics, like GHG reductions, cycling through the same arguments in what has become an increasingly exhausted conversation. And while these indicators are undoubtedly important, this narrow framing constrains the PBD debate. By isolating it to specific metrics, we risk limiting the potential solutions and failing to consider the broader impacts of dietary shifts. Therefore, this essay will move beyond well-established scientific arguments, to apply fresh, alternative framings in which to critically evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of PBDs as a solution to climate change. While not exhaustive, it will first examine how political institutions intersect with the solutional potential of PBDs and the associated risks of the debate becoming apolitical. Secondly, perspectives from justice and decolonial theory will be employed to consider the power dynamics underlying PBDs, addressing issues of cultural resilience and food autonomy. Before finally turning to behavioural understandings of PBDs, investigating how they function as both a form of protest and a tool for reshaping ecological narratives.

Why ‘Plant-Based’?

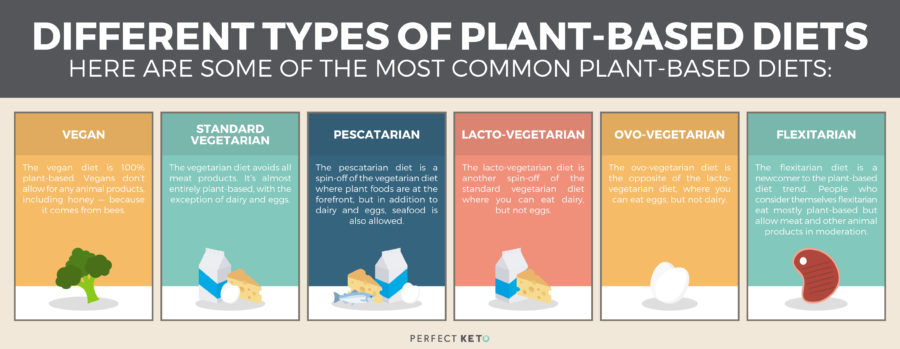

The term ‘plant-based’ evokes a range of interpretations and has been a source of considerable ambiguity in both academic and social discourse (Storz 2022). However, this very ambiguity makes it a valuable lens from which to position ourselves. We shall first adopt the definition provided by Hargreaves et al. (2023), ‘a dietary pattern in which foods of animal origin are totally or mostly excluded.’ This deliberate choice grants the term a holistic character, allowing for a broad yet nuanced understanding that encompasses a spectrum of perspectives. By doing so it aims to avoid rigid definitions that might constrain how we assess PBDs effectiveness or their broader impact. While it may not offer a more precise or immediately actionable answer regarding its role as a climate solution, it allows for a broader discussion, incorporating diverse perspectives and measures of success that might otherwise be overlooked. As such, this framing serves as a valuable complement to ongoing empirical research, enriching the discourse rather than seeking to replace it.

Is it just an issue of politics?

With the global population projected to reach 9.1 billion by 2050, discussions around dietary shifts have become a global imperative (Saxena 2011). A meaningful transition away from animal husbandry would require coordinated action at both national and international levels (Sabaté and Soret 2014). We are already seeing signs of this: Denmark and the Netherlands have heavily invested in plant-based food innovation and related policies (Buxton 2022; Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries of Denmark 2023), and at COP28, two-thirds of the food provided was plant-based— a conference first. So while PBDs are often framed as an individual choice, it’s clear their growing acceptance has begun to shape political institutions in a reciprocal manner.

However, integrating PBDs into the political sphere presents significant challenges. The food sector is characterised by immense market concentration, where stakeholders in the agricultural industry have historically maintained close ties with national decision-makers (Miller and Harkins 2010; Orset and Monnier 2020; Tselengidis and Östergren 2019). Their considerable lobbying power extends not only into political decision-making but into scientific research, consequently shaping narratives and policy agendas (Leroy 2022; Tselengidis and Östergren 2019). Despite their contentious empirical grounding and questionable relationships, governmental narratives and their policy interventions continue to play a pivotal role in PBD adoption (Broeks 2020). As such, political institutions remain not only valuable but potentially transformative, especially if we begin by acknowledging the positionality of science (Latour 1987). Reframing the political landscape in this way opens it up as an opportunistic space: one that facilitates meaningful dialogue and collaboration between scientists, agricultural stakeholders, and governments in the pursuit of more effective PBD policies.

Yet, these discussions are only valuable if they can be realised in praxis. In a climate discourse dominated by scientific jargon and technical data, PBDs must be framed effectively to resonate with stakeholders and the public. Research suggests that strategic shifts in language and narrative construction can support PBD adoption (Papies 2024), particularly by avoiding the label ‘veganism’ in favour of ‘plant-based,’ as the former tends to activate negative associations (Papies 2020). These associations are difficult to ignore as, at least in the West, PBDs have become politically polarised. Framed as a left-leaning lifestyle choice, PBDs are often met with resistance from conservatives, who cite concerns about personal freedom and economic repercussions (Hinrichs et al., 2022; Milfont et al., 2021). This presents a political challenge for PBD policy agreement, as doing so requires not only scientific consensus but a way to bridge ideological divides. This polarisation is unsurprising, as meat consumption is strongly tied to demographic characteristics and closely associated with attitudes and ideologies that favour hierarchical social and environmental relationships (Allen et al., 2000; Hodson and Earle 2018; Whitley, Gunderson, and Charters 2018). As such, support for PBD policies is unlikely to shift through rhetorical framing alone if opposition is rooted in deeply held social and personal values. Consequently, demographic and normative behavioural patterns may help predict policy support, but meaningful adoption is more likely to emerge through personal and emotionally resonant connections.

This is not to say that political discussions around PBDs should be avoided—on the contrary, they invite democratic debate over societal values and encourage dialogue on political alternatives. Yet PBDs occupy a unique position in this discourse, as ideological divisions may be less about political alignment and more reflective of deeper moral frameworks (Grünhage and Reuter 2021). This becomes particularly pertinent when we consider that a significant portion of the debate surrounding PBDs hinges on questions of animal rights, welfare, and moral responsibility. Questions of animal suffering pushes PBDs beyond a purely political or environmental concern and into the realm of moral judgment, where dietary choices become symbols of virtue or vice. A moral framing risks being deeply divisive, splitting individuals into categories of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ based on their dietary decisions. As a result, these conversations risk becoming depoliticised. Not in the sense that they lose political relevance, but rather because they shift the debate away from the structures of human governance and into a domain where conventional policymaking struggles to intervene. After all, how does one legislate moral conviction? This suggests that framing PBDs primarily through a political lens may, paradoxically, undermine their potential as a climate solution by triggering cognitive dissonance among those who reject moralistic arguments.

Do PBDs call for justice?

Historically, meat has been positioned as a marker of power and superiority, a dynamic traceable as far back as the Roman Empire (Sanchez Garcia 2024), where red meat symbolised elevated status in contrast to the PBDs of subjugated populations. This association persisted through European imperial expansion, where meat consumption became entangled with notions of masculinity, progress, and racial hierarchy (Colás 2022). Colonial discourse framed meat-heavy diets as indicative of evolutionary advancement, reinforcing the idea that dependence on animal protein conferred physical and intellectual superiority (Henderson 2011). Cultures that consumed less meat were often portrayed as weaker, feminine, or passive – justifications that helped rationalise their conquest and subjugation (Roy, 2002). Beyond discourse, animal husbandry played a central role in European colonial expansion, providing food, clothing, power, and economic capital to overseas territories (Crosby 1989). Domesticated animals such as pigs and cows were imported to colonies, often displacing native species and reshaping local ecosystems (Gaard 2013). While many indigenous cultures already incorporated meat into their diets, colonial rule altered the specifics of meat consumption, establishing dependence on European livestock. But this was not just about dietary change; colonialism actively transformed human-animal relations, converting non-human life into objects for capitalist accumulation (Montford and Taylor 2020). These European agricultural systems and narratives restructured food production and consumption, therefore denoting a certain ‘ecological imperialism’ that positions global meat consumption as not just a driver of the climate crisis, but as a historically entrenched injustice.

Against this backdrop, the turn toward PBDs can be understood as an act of resistance—one that reclaims autonomy and challenges colonial legacies embedded in global food systems. From an anti-colonial perspective, adopting a PBD is not merely an ecological decision but a rejection of the structures of power that have shaped human-animal relations (Ponce León 2024). Abstaining from meat signifies a refusal to perpetuate the colonial narratives that framed meat consumption as a marker of dominance, progress, and civilization. This shift holds particular significance for indigenous communities, whose ontologies have long emphasised reciprocity, interconnectedness, and mutual respect with nonhuman beings (Kimmerer 2013; Yunkaporta 2019); relations that colonial and capitalist assimilative logics of anthropocentrism and speciesism sought to erode and replace (Montford and Taylor 2020). Therefore, in response, embracing PBDs represents a political and cultural reclamation, a means of resisting what could be described as the ‘inevitable inundation discourse’, the notion that colonial capitalist expansion and its dietary norms are inescapable. It could be argued that the transference to PBDs for some could be understood as a new form of ceremony, reconnecting communities with ancestral knowledge, affirming spiritual ties to the natural world, and prefiguring a decolonial future of coexistence rather than exploitation (Krásná 2024). More broadly, a PBD disrupts dominant Western ecological narratives and by unsettling these paradigms, it creates space for counter-narratives rooted in alternative hierarchies and local ecological knowledge to take hold (Dutta, Azad, and Hussain 2022). Naturally, though we must interrogate this statement more deeply. It would be a mistake to homogenise Indigenous or ‘local’ place-based knowledge, as each tradition carries distinct epistemologies and ontologies (Rarai et al., 2022). Such knowledge is dynamic and context-laden, meaning that while PBDs may open space for post-colonial cultural narratives, their acceptance and production will vary across communities. Some Indigenous groups may advocate for the cultural significance of traditional hunting and fishing as integral to identity, while others view ‘veganism’ itself as an act of decolonial resistance (Krásná 2024). Beyond this, the term ‘plant-based’ itself is rooted in Western-centric discourse. Emerging from Eurocentric frameworks, it carries implicit assumptions about diet and human-animal relations that risk overshadowing alternative cultural perspectives (Gruber, S., 2023). It would seem that imposing a Western-framed dietary solution onto inherently heterogeneous cultures risks simply reproducing the very colonial behaviours it aims to dismantle. If the goal is dietary and ecological self-determination, we must ask whether PBDs—as articulated through Western environmentalism—truly foster resistance or whether they risk becoming another form of imposed normativity.

Calls for justice extend beyond culture, to the material realities of food production. Any idea that PBDs and their products absolve consumers of responsibility for environmental harm is misleading (Alvaro 2017). Western consumers are often disconnected from the consequences of their consumption, as the harm they generate remains unseen and unknowable within global supply chains (Trauger 2022). The notion that an ‘organic’ soybean or ‘sustainable’ palm oil is produced in a purely ethical manner is an illusion. These commodities are entangled in a state- and corporate-administered system that integrates animal feed production with human labour violations and global trade (Trauger 2022). In its wake, this system leaves hunger, exploitation, climate change, species extinction, Indigenous dispossession, and deforestation (Carlson and Garrett 2018; Trauger 2022). Consequently, in its Western iteration, the plant-based movement is materially problematic and continues to be infused with humanist ideals. It suggests that ‘not killing’ a single animal is morally superior to the wholesale destruction of entire ecosystems and local livelihoods. Without addressing this disconnect, PBDs fail to challenge the underlying colonial logic that privileges the moral purity of the (predominantly white, settler) consumer, while neglecting or sidelining the welfare of those most affected by industrial food systems.

Protesting with PBDs

Given the structural entanglements discussed, we might be better positioned to frame PBDs not as a definitive solution, but as a tool for accessing the transformative potential needed to tackle our climate crisis

At their core, PBDs operate on the principle of consumer choice, shifting the power to drive ecological change directly into the hands of individuals (Jackson 2004). In this sense, adopting a PBD can be understood as a form of direct protest as it directly engages with the market-driven structures that underpin our neoliberal world order (Martin and Schouten 2014). However, while this argument has been widely championed (Saari et al, 2021; The Economist 2020) it has also faced rightful critique. Achieving meaningful, large-scale change would require sustained, collective action over an extended period. As discussed in the previous section, an individual’s commitment to a PBD is shaped by diverse cultural and personal motivations, making the movement inherently heterogeneous. This raises questions about both the resilience of such choices and their geographical impact. It would be reductive to assume that an individual adopting a PBD in Nicaragua exerts the same market and global influence as someone in the United States; the structural and economic contexts differ significantly, making direct comparisons difficult, if not impossible, to quantify. Moreover, the rise of ‘vegan’ and ‘vegetarian’ products signals the creation of yet another market. While PBDs aim to challenge the food industry, their growing commodification suggests that, rather than disrupting capitalism, they are being absorbed into it. So by engaging with the market, PBDs risk becoming another avenue for consumption rather than a genuine departure from exploitative systems.

Yet, this is not to suggest that framing PBDs as a tool of protest or activism is ineffective. Rather than viewing the resultant behaviour as the sole solutional measure to climate change, it may be more fitting to understand PBDs symptomatic nature. PBDs, particularly veganism, can be better understood as a direct manifestation of resistance to Western patterns of overconsumption and ecological relations, shaped by identity and community-catalysed narratives (Radnitz, Beezhold and DiMatteo 2015). PBDs are a declaration of one’s morals and beliefs, enabling individuals to align or distinguish themselves from other groups or communities. And so by serving as a social marker of narrative cohesion, belonging and distinction, the fact that this behaviour is creating measurable changes to food choices on the macro level, may denote a deeper ideological and cultural transformation taking root on the micro-scale. Consequently, it may be more accurate to see PBDs as a catalytic tool in fostering and reshaping communities and identities that reject dominant Western conceptions of nature and consumption. Rather than simply opposing conventional dietary norms, PBDs represent a broader challenge to the underlying ideologies that have shaped Western ecological thought—shifting towards alternative mindsets that emphasise interconnectedness, morality, and sustainability. Therefore, if an ideological and cultural shift is believed to be necessary for a sustainable ecological future, then we could imply that PBDs hold significant solutional potential. They not only represent behavioural change, but actively contribute to building new collectives and catalysing a broader paradigmatic shift in how we conceptualise and engage with food, identity, and therefore our natural world.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the debate surrounding PBDs as a climate solution transcends traditional environmental metrics, encompassing complex political, cultural, and ethical dimensions. While PBDs offer clear ecological benefits, their adoption is hindered by deeply entrenched socio-political narratives and power structures. They risk, in their current form, alienating certain communities and reinforcing colonial legacies embedded in global food systems. For true progress, PBDs must be situated within a broader discourse that acknowledges diverse cultural perspectives, promotes food autonomy, and disrupts the hierarchies of global food systems. Ultimately, their true potential may lie in their ability to challenge Western notions of food consumption, serving as a symbol of protest and a catalyst for community-building around these alternative ideologies.

Bibliography

aan den Toorn, S.I., Worrell, E. and van den Broek, M.A., 2020. Meat, dairy, and more: Analysis of material, energy, and greenhouse gas flows of the meat and dairy supply chains in the EU28 for 2016. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 24(3), pp.601-614.

Allen, M.W., Wilson, M., Ng, S.H. and Dunne, M., 2000. Values and beliefs of vegetarians and omnivores. The Journal of social psychology, 140(4), pp.405-422.

Alvaro, C., 2017. Ethical veganism, virtue, and greatness of the soul. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 30(6), pp.765-781.

Buxton, A., 2022. Dutch Government Awards €60 Million To Domestic Cellular Agriculture Ecosystem, Green Queen. Accessed April 7 2025 from: https://www.greenqueen.com.hk/netherlands-60-million-cellular-agriculture/

Broeks, M.J., Biesbroek, S., Over, E.A., Van Gils, P.F., Toxopeus, I., Beukers, M.H. and Temme, E.H., 2020. A social cost-benefit analysis of meat taxation and a fruit and vegetables subsidy for a healthy and sustainable food consumption in the Netherlands. BMC public health, 20, pp.1-12.

Carlson, K.M. and Garrett, R.D., 2018. Environmental impacts of tropical soybean and palm oil crops. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science.

Colás, A., 2022. Food, multiplicity and imperialism: Patterns of domination and subversion in the modern international system. Cooperation and Conflict, 57(3), pp.384-401.

Crippa, M., Solazzo, E., Guizzardi, D., Monforti-Ferrario, F., Tubiello, F.N. and Leip, A.J.N.F., 2021. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nature food, 2(3), pp.198-209.

Crosby, A. W., 1989. Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900-1900. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dudley, N. and Alexander, S., 2017. Agriculture and biodiversity: a review. Biodiversity, 18(2-3), pp.45-49.

Dutta, U., Azad, A.K. and Hussain, S.M., 2022. Counterstorytelling as epistemic justice: Decolonial community‐based praxis from the global south. American journal of community psychology, 69(1-2), pp.59-70.

Eshel, G., Shepon, A., Makov, T. and Milo, R., 2014. Land, irrigation water, greenhouse gas, and reactive nitrogen burdens of meat, eggs, and dairy production in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(33), pp.11996-12001.

Fresán, U. and Sabaté, J., 2019. Vegetarian diets: planetary health and its alignment with human health. Advances in nutrition, 10, pp.S380-S388.

Gaard, G., 2013. Toward a Feminist Postcolonial Milk Studies. In American Quarterly, 65(3), pp.595-618.

Gerber, P.J., Steinfeld, H., Henderson, B., Mottet, A., Opio, C., Dijkman, J., Falcucci, A. and Tempio, G., 2013. Tackling climate change through livestock: a global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities (pp. xxi+-115).

Gruber, S., 2023. The Power of Ecological Rhetoric: Trans-Situational Approaches to Veganism, Vegetarianism, and Plant-Based Food Choices. In The Rhetorical Construction of Vegetarianism (pp. 23-44). Routledge.

Grünhage, T. and Reuter, M., 2021. What makes diets political? Moral foundations and the left-wing-vegan connection. Social Justice Research, 34(1), pp.18-52.

Hallström, E., Carlsson-Kanyama, A. and Börjesson, P., 2015. Environmental impact of dietary change: a systematic review. Journal of cleaner production, 91, pp.1-11.

Hargreaves, S.M., Rosenfeld, D.L., Moreira, A.V.B. and Zandonadi, R.P., 2023. Plant-based and vegetarian diets: an overview and definition of these dietary patterns. European journal of nutrition, 62(3), pp.1109-1121.

Harris, F., Moss, C., Joy, E.J., Quinn, R., Scheelbeek, P.F., Dangour, A.D. and Green, R., 2020. The water footprint of diets: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Advances in Nutrition, 11(2), pp.375-386.

Hathaway, M.D., 2016. Agroecology and permaculture: addressing key ecological problems by rethinking and redesigning agricultural systems. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 6, pp.239-250.

Henderson, J., 2011. ‘No Money, But Muscle and Pluck’: Cultivating Trans-Imperial Manliness for the Fields of Empire, 1870–1901. Making It Like A Man: Canadian Masculinities in Practice, pp.17-37.

Hinrichs, K., Hoeks, J., Campos, L., Guedes, D., Godinho, C., Matos, M. and Graça, J., 2022. Why so defensive? Negative affect and gender differences in defensiveness toward plant-based diets. Food Quality and Preference, 102, p.104662.

Hodson, G. and Earle, M., 2018. Conservatism predicts lapses from vegetarian/vegan diets to meat consumption (through lower social justice concerns and social support). Appetite, 120, pp.75-81.

IPCC, 2019: Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems

Jackson, T., 2004. Negotiating Sustainable Consumption: A review of the consumption debate and its policy implications. Energy & Environment, 15(6), pp.1027-1051.

Kimmerer, R.W., 2013. Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Milkweed editions.

Kinley, R.D., Martinez-Fernandez, G., Matthews, M.K., de Nys, R., Magnusson, M. and Tomkins, N.W., 2020. Mitigating the carbon footprint and improving productivity of ruminant livestock agriculture using a red seaweed. Journal of Cleaner production, 259, p.120836.

Krásná, D., 2024. “Decolonize your Diet”: Politics of Consumption and Indigenous Veganism in Eden Robinson’s The Trickster Trilogy. ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, 31(2), pp.312-332.

Latour, B., 1987. Science in action: How to follow scientists and engineers through society. Harvard university press.

Leroy, F., Abraini, F., Beal, T., Dominguez-Salas, P., Gregorini, P., Manzano, P., Rowntree, J. and Van Vliet, S., 2022. Animal board invited review: Animal source foods in healthy, sustainable, and ethical diets–An argument against drastic limitation of livestock in the food system. Animal, 16(3), p.100457.

Macdiarmid, J.I., 2022. The food system and climate change: are plant-based diets becoming unhealthy and less environmentally sustainable?. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 81(2), pp.162-167.

Martin, D.M. and Schouten, J.W., 2014. Consumption-driven market emergence. Journal of Consumer research, 40(5), pp.855-870.

Milfont, T.L., Satherley, N., Osborne, D., Wilson, M.S. and Sibley, C.G., 2021. To meat, or not to meat: A longitudinal investigation of transitioning to and from plant-based diets. Appetite, 166, p.105584.

Miller, D. and Harkins, C., 2010. Corporate strategy, corporate capture: food and alcohol industry lobbying and public health. Critical social policy, 30(4), pp.564-589.

Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries of Denmark., 2023. Danish Action Plan for Plant-Based Foods

Montford, K.S. and Taylor, C., 2020. Colonialism and animality. Colonialism and Animality, p.1.

Orset, C. and Monnier, M., 2020. How do lobbies and NGOs try to influence dietary behaviour?. Review of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Studies, 101(1), pp.47-66.

Papies, E.K., Davis, T., Farrar, S., Sinclair, M. and Wehbe, L.H., 2024. How (not) to talk about plant-based foods: Using language to support the transition to sustainable diets. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 83(3), pp.142-150.

Papies, E.K., Johannes, N., Daneva, T., Semyte, G. and Kauhanen, L.L., 2020. Using consumption and reward simulations to increase the appeal of plant-based foods. Appetite, 155, p.104812.

Ponce León, J. J., 2024. Popular and Decolonial Veganism: Animal Rights, Racialized and Indigenous Subjectivities in Latin America. Relations – Beyond Anthropocentrism, 12(1), pp.49-70.

Radnitz, C., Beezhold, B. and DiMatteo, J., 2015. Investigation of lifestyle choices of individuals following a vegan diet for health and ethical reasons. Appetite, 90, pp.31-36.

Rarai, A., Parsons, M., Nursey-Bray, M. and Crease, R., 2022. Situating climate change adaptation within plural worlds: The role of Indigenous and local knowledge in Pentecost Island, Vanuatu. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 5(4), pp.2240-2282.

Roy, P., 2002. Meat–eating, masculinity, and renunciation in India: a Gandhian grammar of diet. Gender & History, 14(1), pp.62-91.

Saari, U.A., Herstatt, C., Tiwari, R., Dedehayir, O. and Mäkinen, S.J., 2021. The vegan trend and the microfoundations of institutional change: A commentary on food producers’ sustainable innovation journeys in Europe. Trends in food science & technology, 107, pp.161-167.

Sabaté, J. and Soret, S., 2014. Sustainability of plant-based diets: back to the future. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 100, pp.476S-482S.

Sanchez Garcia, G., 2024. We are what we eat: Exploring the formation of provincial identities through meat production and consumption in the Roman Empire (Master’s thesis).

Saxena, A.M., 2011. The vegetarian imperative. JHU Press.

Scialabba, N.E.H. and Müller-Lindenlauf, M., 2010. Organic agriculture and climate change. Renewable agriculture and food systems, 25(2), pp.158-169.

Springmann, M., Clark, M., Mason-D’Croz, D., Wiebe, K., Bodirsky, B.L., Lassaletta, L., De Vries, W., Vermeulen, S.J., Herrero, M., Carlson, K.M. and Jonell, M., 2018. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature, 562(7728), pp.519-525.

The Economist., 2020. Interest in veganism is surging. The Economist Group. Accessed April 7, 2025, from https://www.economist.com/graphicdetail/2020/01/29/interest-in-veganism-is-surging

Trauger, A., 2022. The vegan industrial complex: the political ecology of not eating animals. Journal of Political Ecology, 29(1), pp.639-655.

Whitley, C.T., Gunderson, R. and Charters, M., 2018. Public receptiveness to policies promoting plant-based diets: framing effects and social psychological and structural influences. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 20(1), pp.45-63

Willett, W., 2018. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits, Nature, 562, pp. 519–25.

Storz, M.A., 2022. What makes a plant-based diet? A review of current concepts and proposal for a standardized plant-based dietary intervention checklist. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76(6), pp.789-800.

Tselengidis, A. and Östergren, P.O., 2019. Lobbying against sugar taxation in the European Union: analysing the lobbying arguments and tactics of stakeholders in the food and drink industries. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 47(5), pp.565-575.

Van Vliet, S., Kronberg, S.L. and Provenza, F.D., 2020. Plant-based meats, human health, and climate change. Frontiers in sustainable food systems, 4, p.555088.

Yunkaporta, T., 2019. Sand talk: How Indigenous thinking can save the world. Text Publishing.