Part 1: Climate change is threatening our food security. Could emerging technologies be an answer?

As we enter 2024, the spectre of climate change continues to loom large in many of our minds. The unstable geopolitical situation across the world makes the prospect of coordinated international action on such a multifaceted issue seem more unlikely. Adding to our woes, the high prevalence of conflict introduces competing incentives for national issues like energy security, food security, and defence that could delay much needed progress towards net zero. 2023 proved to be the hottest year on record, with global average temperatures reaching 1.48oC above pre-industrial levels according to the EU’s climate service. It is highly likely that temperature rises will exceed the 1.5oC threshold agreed at the Paris climate summit before the close of this century. As temperatures climb and the effects of climate change are felt more significantly across the globe, humanity will need to turn to novel technologies as it adapts to unprecedented weather conditions. In this series, I will examine how scientists may be able to harness genetic engineering technology and leverage existing genomic information using artificial intelligence to adapt agricultural production to climate change-related challenges. In the first article of the series, we start at the beginning: thematically identifying the problems future farmers will face.

With global population expected to rise to nearly 10 billion by the middle of the 21st century (1), the world faces a pressing imperative for agricultural innovation. Currently, crop yields can provide enough food for most of the global population. However, the trajectory of agricultural productivity is concerning, with yields plateauing and declining in the face of climate change and the reduced accessibility of arable land. To feed 10 billion people, agricultural yields will need to increase by an estimated 60% (2). However, the challenge lies not only in scaling up food production to meet escalating demand but also in pre-emptively addressing the multifaceted threats of climate change, environmental degradation and loss of biodiversity, and the socio-economic factors that exacerbate the vulnerabilities of specific populations to agricultural crises.

By the end of 2022, an estimated 735 million people were afflicted by chronic hunger, characterized by sustained insufficient caloric intake. The distribution of these populations is unequal on a global scale; Africa is the worst affected continent, with approximately 20% of the population facing chronic hunger (3). Moreover, nearly 2 billion individuals were estimated to have micronutrient deficiencies in 2014 (4). Some models have estimated that malnutrition-related fatalities could double by 2050 if the availability of fruits and vegetables continues to wane (5). Our capacity to feed this growing populace is further imperilled by climate change’s relentless march, as articulated with alarming clarity in the IPCC 2022 Climate Report. We stand on brittle ground; as much as 20% of our planet’s surface is already threatened by soil degradation (6), with its fertility reduced by the loss of essential nutrients. Current strategies employed to reclaim these lands, including intensive use of fertilizers and soil tilling, serve to increase carbon emissions associated with agricultural practices, ensnaring us in a vicious feedback loop.

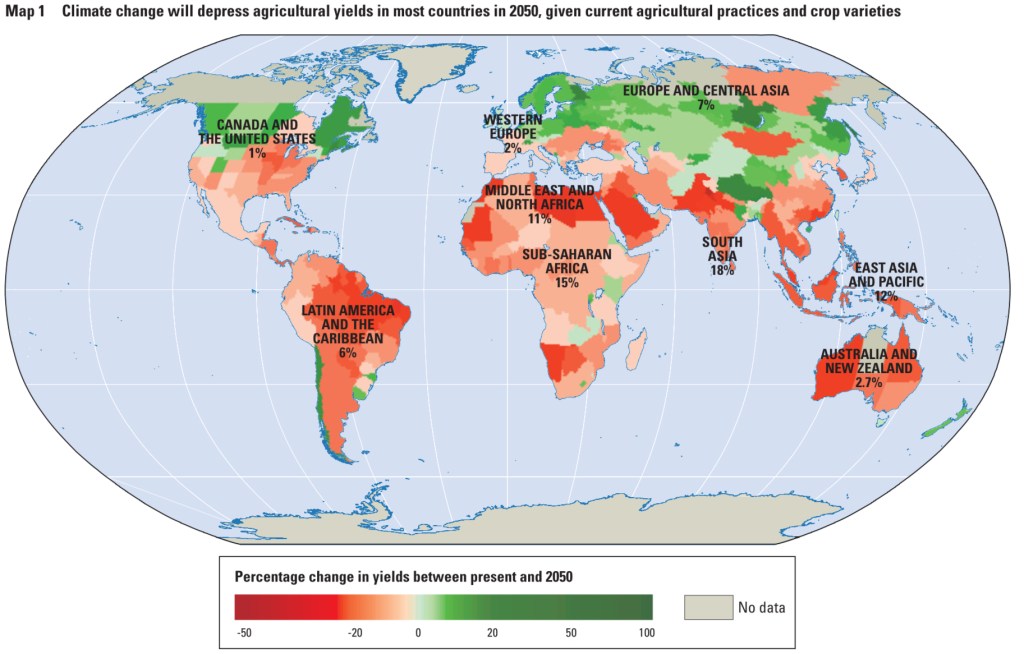

As the global temperature rises, so too does the vulnerability of our crops. Desertification, droughts, floods, and violent storms all threaten annual harvests, but climate change is also anticipated to result in a global net loss of arable land, reducing agricultural production over the long-term. This is compounded by the anticipated growth of human settlements, which will reduce the land available for farming (7). In addition, agricultural yields of current staple crops are expected to decrease in most regions by 2050 (8; Figure 1). Current modelling indicates that the negative consequences of climate change will not be distributed evenly, with lower latitude regions anticipated to bear the brunt of the impact, in terms of both arable land loss and decreased agricultural yields.

Higher atmospheric CO2 concentrations also have a negative effect upon the nutritional quality of agricultural crops, despite also being growth-enhancing (9). For example, an IPCC special report demonstrated wheat grown at projected late 21st century CO2 levels has been found to have reduced protein and mineral content, including iron and zinc. Current projections indicate that by 2050 an additional 1.9% of the global population will become zinc-deficient, and another 1.3% will be protein deficient if the current trajectory of CO2 emissions is not altered (10). Gene engineering may therefore play a role in reducing global malnutrition rates beyond simply enhancing yields. Techniques from metabolic engineering and synthetic biology allow the modification of gene networks and the introduction of novel metabolic pathways (11), modulating the production of nutritional metabolites in ways that are advantageous for humans.

Beyond the immediate impacts on agricultural productivity, the loss of arable land will have secondary negative impacts on biodiversity and conservation, particularly in tropical regions. As farmers in these regions face decreasing yields and restricted land availability, the likelihood of human agricultural encroachment into our grasslands, rainforests, and savannahs rises. For example, in Brazil cattle ranching using “slash-and-burn” methods has historically been the main driver of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest (12). Strong increases in soybean production in the Cerrado savannah have also resulted in significant deforestation in the region over recent years, with deforestation rates estimated to have increased by 17.5% between 2018 – 2021 (13). The destruction of wilderness in tropical regions has a significant impact on global biodiversity, as millions of species are found within these ecosystems making them some of the most biodiverse regions on Earth. New medicines, materials, and foodstuffs are often discovered or derived from these biodiversity hotspots. Ecological collapse of these systems would be detrimental for human civilisation as it removes these sources of novel goods, and increases human reliance upon known medicines, foodstuffs and materials (14). The complex interactions between ecosystems on a global scale is also not well understood, and the collapse of tropical ecosystems may have unpredictable consequences for people living in other regions.

Conservation and rewilding practices are employed to protect biodiversity and our planet’s precious natural resources. Over the last few decades, conservation practices have been increasing in frequency, driven by greater understanding of ecology and the introduction of new legislation. Conservation science has also been growing at a considerable rate, and there are now hundreds of ecology journals representing different subdisciplines (15). While this progress is positive for the environment and mitigating the negative impacts of climate change, most conservation techniques necessarily restrict the amount of land available for agriculture through preventing the expansion of farmland. To meet the demands of a growing population while maintaining an acceptable level of biodiversity, farming will therefore have to simultaneously enlarge crop yields while adopting environmentally friendly agricultural practices. This hurdle seems even higher when considering that yields appear to be plateauing or decreasing, and that the intensive farming methods used to maximize yields historically have resulted in significant soil degradation and environmental damage (16). This will require the development of completely novel techniques for agricultural intensification within an ever-constricting timeframe if we are to avoid the worst impacts of climate change on global food security.

Climate change is anticipated to cause global yield reductions due to higher rates of disease amongst plants. Increasing temperatures, CO2 concentrations, and changes to humidity and rainfall are capable of altering and promoting the spread of crop pathogens. It has been estimated that plant diseases already result in an annual cost of $220bn USD in crop losses (17), and that potential yield gains in the next 5 decades could be offset by increased losses due to climate-mediated disease spread (18). Climate and ecological changes in combination with the extensive use of monocultures in modern agriculture are likely to facilitate the emergence of crop pathogens capable of extending beyond their normal geographical range.

This is further exacerbated by the necessity for international trade. The introduction of new pathogens to crops that have not co-evolved with them can often lead to devastating disease outbreaks in previously disease-free regions. While the influence on individual climatic factors (e.g. temperature) on major crop pathogens is partially understood, there is currently limited understanding of how interactions between multiple climatic conditions and agricultural practices may affect crop diseases. However, several studies have demonstrated that combination effects involving multiple disease-promoting factors can have more significant consequences than individual factors (19, 20). While further research is needed, climate change is likely to drive an increase in frequency and severity of at least some crop diseases. This will further increase pressure on food security in affected regions.

Unfortunately, many of the regions worst affected by climate change are already facing significant challenges of food insecurity and poverty (21), and the populations inhabiting them are often highly vulnerable to climate-related disasters. These communities are likely to become less resilient to climate shocks as the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events increases. This lack of resilience will be exacerbated by insecure food supplies. If this proves correct, the political, social, and economic ramifications of such an outcome will be severe. Increasing food insecurity in poorer regions of the world also has knock-on effects: increasing food prices and reliance on imports decreases social mobility, drives political instability, increases migratory pressure, and increases the risk of physical violence and resource conflicts.

These knock-on effects can also enter feedback loops, exacerbating the problem. For example, imagine the following scenario: High food prices and low social mobility exacerbate civil instability within a country. Eventually civil conflict erupts, resulting in the devaluation of the nation’s currency in international markets, while also lowering domestic agricultural production. This leads to an increase in the price of imported food, further driving up the costs of food and thus helping to sustain social instability.

Beyond the moral imperative to prevent and reduce human suffering, wealthy nations have additional incentives to invest in developing climate-resilient crops. In the interconnected world of the 21st century it is increasingly clear that nations are not capable of maintaining current living standards without the stability and prosperity of their neighbours. Devastating crop failures in Asia or Africa would be felt strongly in Europe or North America. Factor in the potential for resource conflicts wreaking havoc with international supply chains, or the societally destabilising effects of multimillion person climate-driven migration, and the wider benefits of climate-resilient crops for wealthy countries become increasingly evident. Ensuring global food security acts to increase national security for all countries, and promote international peace, prosperity and cooperation.

In the subsequent pieces in this series, I will try to explain why I believe genetic engineering technologies can function in combination with advances in artificial intelligence and other fields to enable the creation of new and better crops. I will examine the current state of play in genetic agriculture, highlighting the important advances and limitations, and also try to assess future avenues for research.

Bibliography

- FAO 2017, The future of food and agriculture – Trends and challenges, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome

- Springmann, M., Clark, M., Mason-D’Croz, D. et al. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature 562, 519–525 (2018)

- FAO 2023, The future of food and agriculture – Trends and challenges, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome

- Von Grebmer, K., Saltzman, A., Birol, E., Wiesmann, D., Prasai, N., Yin, S., et al. 2014 Global Hunger Index: The Challenge of Hidden Hunger (Washington, DC), 56 (2014)

- Springmann, M., Mason-D’Croz, D., Robinson, S., Garnett, T., Godfray, H. C. J., Gollin, D., et al. Global and regional health effects of future food production under climate change: a modelling study. Lancet 387, 1937–1946 (2016)

- Hussain, M. I., Abideen, Z., & Qureshi, A. S. Soil Degradation, resilience, restoration and sustainable use. E. Lichtfouse (Ed.), Sustainable agriculture reviews 52, 335–365 (2021)

- Zhang, X. & Cai, X. Climate change impacts on global agricultural land availability. Environmental Research Letters, Vol. 6. (2021)

- World Bank “World Bank development report 2010: Development and climate change” (2010)

- Ebi, K.L. and Loladze, I. Elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations and climate change will affect our food’s quality and quantity. The Lancet Planetary Health, 3(7), 283–284 (2019)

- Smith, M. R., and Myers, S. S. Impact of anthropogenic CO2 emissions on global human nutrition. Nature Climate Change 8, 834–839 (2018)

- Zhu, Q., Wang, B., Tan, J., et al. Plant Synthetic Metabolic Engineering for Enhancing Crop Nutritional Quality. Plant Communications, 1(1), 100017 (2020)

- Santos AMD, Silva CFAD, Almeida Junior PM, et al. Deforestation drivers in the Brazilian Amazon: assessing new spatial predictors. Journal of Environmental Management. 294:113020 (2021)

- https://www.wwf.org.br/?84261/Deforestation-in-the-Amazon-remains-at-high-levels-with-a-rate-of-11568-km2-in-2022#:~:text=The%20annual%20rate%20of%20deforestation,August%202021%20and%20July%202022. World Wide Fund for Nature. Accessed Nov. 26, 2023

- Howes, M. et al. Molecules from nature: Reconciling biodiversity and drug discovery. New Phytologist, Plants, People, Planet. 2:463–481 (2020)

- Anderson, C. et al. Trends in ecology and conservation over eight decades, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 19:5:274-282 (2021)

- Friedrich, T., Derpsch, R., & Kassam, A. Overview of the Global Spread of Conservation Agriculture. Field Actions Science Reports Special Issue 6 (2012)

- Chaloner, T. M., Gurr, S. J. & Bebber, D. P. Plant pathogen infection risk tracks global crop yields under climate change. Nature Climate Change 11, 710–715 (2021)

- Singh, B.K., Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Egidi, E. et al. Climate change impacts on plant pathogens, food security and paths forward. Nature Reviews Microbiology 21, 640–656 (2023)

- Suzuki, N., Rivero, R.M., Shulaev, V., Blumwald, E. and Mittler, R. Abiotic and biotic stress combinations. New Phytologist, 203: 32-43 (2014)

- Sewelam, N., El-Shetehy, M., Mauch, F. et al. Combined Abiotic Stresses Repress Defense and Cell Wall Metabolic Genes and Render Plants More Susceptible to Pathogen Infection. Plants 10:1946 (2021)

- Wheeler, T., & von Braun, J. Climate change impacts on global food security. Science 341(6145), 508–513 (2013)